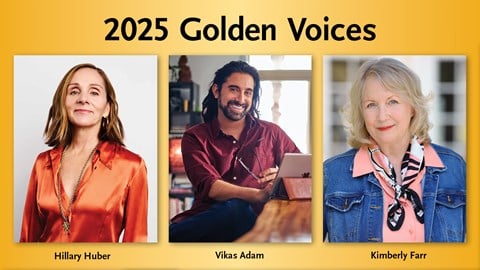

Kimberly Farr has had a long and distinguished career as an actor on stage and screen and as a celebrated audiobook narrator. A gifted performer with an impressive range, Kimberly has brought characters and stories to life, in fiction and nonfiction alike. Whether it’s Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge novels, Joan Didion’s essays, the memoir of Julia Child, or the poetry of Mary Oliver, Kimberly captures their voices with rare clarity, nuance, and a deep understanding of language. So it’s no surprise that AudioFile named her a 2025 Golden Voice narrator. In this bonus episode, host Jo Reed and Kimberly Farr speak about Kimberly’s path to audiobook work and what it means to inhabit every voice on the page.

Partial transcript:

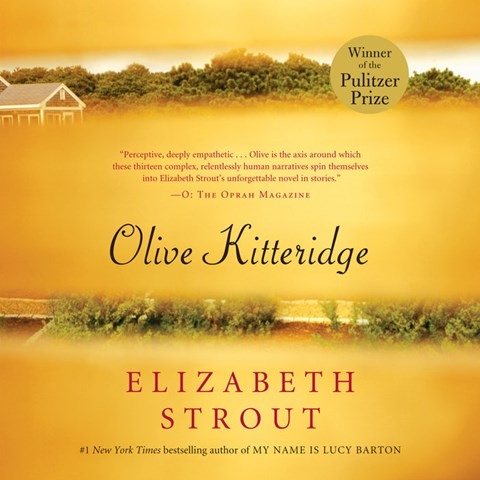

Jo Reed: How do you prepare for narrating fiction, for example, and why don't we start with Elizabeth Strout? You’ve narrated most of her books, including all the books in the series that takes place in this little town in Maine that began with the Pulitzer Prize winner OLIVE KITTERIDGE.

Kimberly Farr: Elizabeth Strout. What a brilliant, brilliant writer she is. Fiction is fun. It's a lot of fun. My process is similar for fiction and nonfiction. First of all, you have to read the material, obviously, you have to read it all. For fiction, I start with the text and a notebook, and I start writing down what page what character first appears on. I write down all of the stuff that other characters say about that character, and I write down stuff that I observe about the character him or herself. If there's a dialect involved or an accent, I have to research that, if I can't already do it. That is really fun. I love doing accents. Interestingly enough, for Elizabeth's books, most of them take place in Maine, Elizabeth did not want a Down East accent. She specifically told Kelly Gildea, the director and producer of those books, that she did not want a Down East accent, which I found really interesting

Kimberly Farr: Elizabeth Strout. What a brilliant, brilliant writer she is. Fiction is fun. It's a lot of fun. My process is similar for fiction and nonfiction. First of all, you have to read the material, obviously, you have to read it all. For fiction, I start with the text and a notebook, and I start writing down what page what character first appears on. I write down all of the stuff that other characters say about that character, and I write down stuff that I observe about the character him or herself. If there's a dialect involved or an accent, I have to research that, if I can't already do it. That is really fun. I love doing accents. Interestingly enough, for Elizabeth's books, most of them take place in Maine, Elizabeth did not want a Down East accent. She specifically told Kelly Gildea, the director and producer of those books, that she did not want a Down East accent, which I found really interesting

JR: So how do you arrive at voicing their characterizations? I mean, or the process for determining the voice for any given character, but especially with Elizabeth's books, because you're picking up somebody who wandered into a scene three books ago, and suddenly here he is. It's his point of view that's dropping this story.

KF: Years ago I listened to Emily Rankin read a book about the Alcott family, Louisa May and her sibs, and here's a group of people who share geography and family and age, and how do you make those four voices sound different so that when one of them is speaking, you know exactly who it is? And Emily did such a brilliant job of that. And at the time I was thinking, how is she doing that? And then I realized that each character, if you listen, has a voice of her or his own. And so when I'm preparing fiction, I do my darnedest to climb into that person's head. I can't think of a better way of putting it.

There are certain technical things you can do to make a character stand out. You can play with the pitch of the voice. Is it high? Is it low? Is it medium? Is it loud? Does the person talk like this? Is the person scared? Those things are relatively easy to adjust, but to understand and replicate what the character is thinking and where they're coming from, what makes them say this thing in this particular moment, that I think you just have to get out of its way. You just have to let it happen.

One of my weaknesses as an actor was that I was so intent on being perfect that I let that get in the way of being good. And I had planned and rehearsed every moment in the theater, which is possible. But then you sit down with a text that's three or four or five hundred pages long, and there's no way to rehearse that. No way. And so you have to trust yourself, and you have to trust the material and you just have to say, okay, this is going to be okay. It's going to be good. It's going to be great. I think that's the most valuable thing that audiobooks taught me as a performer

JR: We've mentioned you narrate a lot of nonfiction as well as fiction, but you prepare pretty much the same way for both?

KR: Well, up until fairly recently, there was only one voice in nonfiction, and that was the author's voice. And lately they've started to ask us narrators to give the people who are speaking some sort of—characterization is too extreme, but they're asking for shading, so you know who's speaking other than the author. And that's kind of interesting. I think, again, I have to keep coming back to the fact that I am in service of the material. I am there to speak for the author the best way I can and not to impose my stuff on anything. I'm just, I am the throat. I am going from the author's brain into the brain of the listener. And my job is to make that material as compelling and clear and interesting and the author's voice as I can.

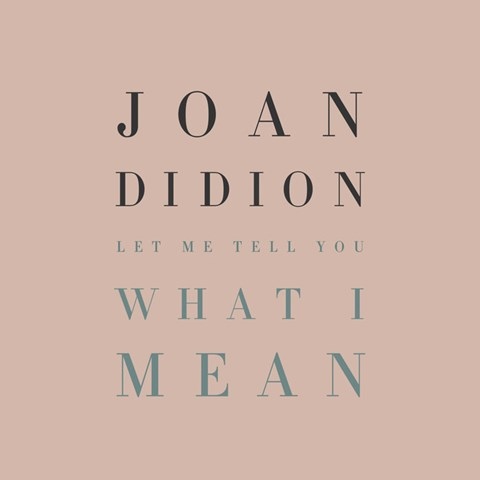

JR: With nonfiction, I'm thinking of Joan Didion's book of essays that you narrated, LET ME TELL YOU WHAT I MEAN. I think the challenges of narrating essays, and essays by someone as well-known as Didion, I would find it a little bit formidable.

JR: With nonfiction, I'm thinking of Joan Didion's book of essays that you narrated, LET ME TELL YOU WHAT I MEAN. I think the challenges of narrating essays, and essays by someone as well-known as Didion, I would find it a little bit formidable.

KF: Well, here's an interesting bit of trivia. When I was young, I used to do a Joan Didion piece as an audition piece. Back in the day, they used to say, bring in an audition piece. They wouldn't say they wanted to hear from the script that they were producing. They wanted you to come in, and I have an actor friend who used to call them your party piece. And I absolutely loved Joan Didion. And she had a collection of essays that was titled SLOUCHING TOWARDS BETHLEHEM. And in that collection of essays is one called “Goodbye to All That.” And it's about a young woman, herself, coming to New York as a very young person, and how New York changed her. And that piece just really spoke to me, and I did it for years as an audition piece. So when I was asked to read her book, I was thrilled, absolutely thrilled, because again, her cadence is one that I understand in some organic way.

—

Listen to their full conversation on our Behind the Mic podcast.

Photo by Robert Kazandjian